With all the ups and downs of raising a child on the autism spectrum, there are some “mantras” that I have embraced to help me stay centered. Take the notion of equanimity, for example. I was reintroduced to the word in an ethics class five or six years ago. And here is the meaning: Mental calmness, composure, and evenness of temper, especially in a difficult situation.

With all the ups and downs of raising a child on the autism spectrum, there are some “mantras” that I have embraced to help me stay centered. Take the notion of equanimity, for example. I was reintroduced to the word in an ethics class five or six years ago. And here is the meaning: Mental calmness, composure, and evenness of temper, especially in a difficult situation.

It is a hard sell, to be sure. There are countless difficult situations that we, as parents, find ourselves in. It might be easier to leap tall buildings in a single bound, especially given how wrenching and overwhelming some of those situations are. And, in times of extreme stress, it might be far better to have a safe place to lose our mental composure, if only for a short while. Or, at least, that’s how I feel in the moment.

And yet, equanimity does help me survive and thrive, particularly in light of more every-day challenges. One of those challenges, one that is often discussed by the parents in my groups, is the seemingly stress-free act of going to a public place with our children. “Simple” errands can become catastrophes. Our children can have a sudden meltdown in the vegetable aisle of the grocery store, or start screaming in the serene setting of a library. These experiences can really unhinge us, making us a little gun-shy about the prospect of future adventures.

But we need to soldier on, and, more importantly, our children need to learn how to navigate in these settings. So we persevere. We learn to take the seemingly disapproving reactions of strangers with a grain of salt. We get savvier about how to prepare our children for various outings. And, hopefully, we grow in equanimity.

I like to feel that I’ve made headway in developing equanimity. My son is improving in his ability to monitor himself, and I have a lot more experience, and confidence, in public situations. But I have to admit that the state of mental calmness I seek often eludes me. Instead, I find myself tensed up and ready to intervene at a moment’s notice. Sometimes I pride myself that it pays to be in a state of high alert. I might intercept my child before he goes over to hug an unsuspecting child, or smooth over an awkward verbal exchange. But more often than not, I pay a big price for my vigilance.

That is exactly what happened about a year ago, when I went with my son to a party.

I knew that there would be kids at the party who already know my son, and who have similar issues. I should have been able to relax. But old habits die hard, and, without even being aware of it, I was in hyper-vigilant mode, geared for the worst, ready to leap to “help”, to “facilitate”.

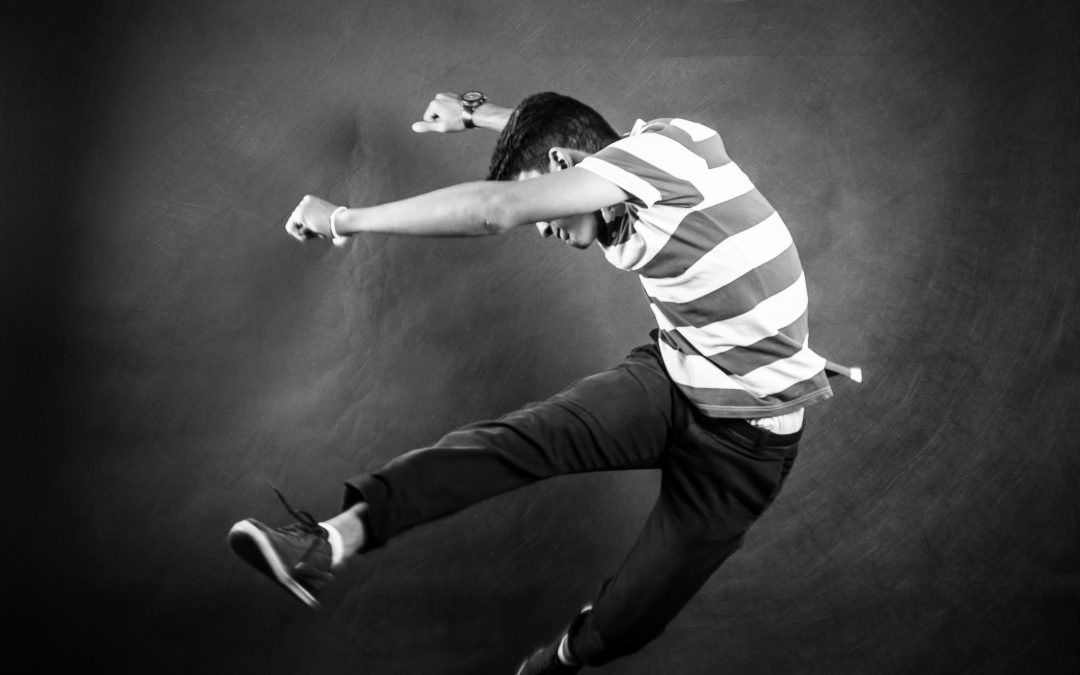

There was music playing at the party, one of the Top 40 songs that my son loves. I was talking to another parent, and I heard my son, at a distance, asking a girl, “Hey, want to see me dance?”

Then, to my horror, I saw my son lie on his back and start kicking his legs around. I didn’t know what he was doing, but it looked really bad.

My inner alarm went off. I interrupted the conversation I was having, and hurried over. I wanted to tell my son to stop that instant. I wanted to do whatever damage control might be needed with the girl he was speaking to. I wanted to leave the party.

But I didn’t make it to my son first. And that was extremely fortunate.

The first person to reach my son was a friend and teacher who works with special needs kids, and knows my son. “Hey Noah,” she said with a smile, “That is really cool break-dancing!”

Noah smiled at her comment. So did the girl he was with.

Break-dancing! That’s what my son was doing.

What a lesson for me. Here was a whole new slant on equanimity: a recognition that being in a centered place (or not) affects the way I look at things! I realize that when I am not in a place of equanimity, my vision and perspective are distorted. I miss really seeing my son, and learning what his behavior is trying to teach me.

I recently read a piece by Shannon Des Roches Rosa which is published in her wonderful book called the Thinking Person’s Guide to Autism. She emphasizes that “Behavior is communication. That’s it. That’s all. That’s everything.” She goes on, “If you put your mental backbone into behavioral awareness, into trying to understand why a person with autism.. behaves the way he or she does…that is when the connections will truly happen.”

What I’ve gained from the break-dancing episode is the realization that, when I can have a little more equanimity, I can see things in a more balanced way. There are so many things that I would like to change, but first, I need to really understand what is going on. Equanimity gives me the ability to learn from a situation. And that gives me a sense of hope and empowerment.

So, when I’m somewhere with my son, I’m learning to ask myself a new question: “Is it the end of the world, or just break-dancing?” Because, if my son is a budding break-dancer, I don’t want to get in his way.